Well, enough about me. Let’s talk about you. What do you think about me?

– Bette Midler

The odd couple

Every time I sit at my desk to tackle a new project, I find myself facing those two, the odd couple: brands and their targets.

The brands always introduce themselves first. They’ve never made a mistake. They’re successful: attractive, funny, modern yet traditional, passionate, full of values, professional, authentic. Naturally, with such excellence, they’ve become market leaders.

Brands send us a brief because they want to win the hearts of their better halves—their targets.

A brief often spends ample time stressing the brand’s main assets. They present their product, and what a product it is! Detailed descriptions cover features, USPs, novelty elements and the underlying philosophy. They talk about their heritage, vision and mission. Already on the first date, some even rave about their purpose.

Love rivals

Sometimes, a brief ends here. We already have all the necessary information, don’t we?

Occasionally, some briefs venture further, admitting to some of the brand’s gnawing concerns. For example, the target’s heart might be courted by other potential suitors — the competitors, an odd breed described in the same terms and language brands employ to describe themselves: their narratives, their positioning, their communication angles. We are often asked to contribute with our own point of view on the subject(s), to spy on them and duly report our findings in a benchmark.

Ideal, perfect, elusive

Then there are detailed briefs where the brand’s obscure object of desire is gradually framed through handy descriptors. Italians. Athletes. Women under 50. Residents of the Center and South (islands included). High-spending professionals. Millennials. Zoomers.

Some brands dig deeper, painting a refined portrait of their desired target profiles. They aim to conquer enterprising innovators, wellness-obsessed moms, committed pescatarians and extroverted programmers.

Of these people, brands list trigger and pain points, supported by short bios somewhat related to the products they consume. After spending some time on these profiles, a clear pattern often emerges. Or rather, hints of a story—of self-projections and idealizations, of perfect partners who can’t wait to welcome these brands as enablers in their lives. This is why the hardest part of every research project is attempting to give form and personality to this frequently elusive target. The first step is usually making do without the gunsight and, in general, the whole ‘target’ concept, drawn from an outdated and out-of-touch belligerent lingo.

The proverbial “spark”

With every major project, we devote the better part of our strategic analysis to observing and actually talking to people. And every time we do this, suddenly the world in which we are constantly immersed — made up of brand lovers, ambassadors, evangelists and gullible individuals seduced by a well-crafted claim or an incisive line — that world disappears, making way for people who go about their lives doing something almost unheard of for those in our line of work. They don't think about advertising.

When people welcome brands and their products into their lives, they don’t think about a certain brand promise or brand essence, but rather about what that product means to them. There’s a catch, thought. Rarely is our crucial piece of information spelled out in clear letters. It has to be parsed critically, reading between the lines.

We notice this by reading conversations where brands are mentioned — real conversations, though, which are but a small portion of those captured by our conversation analysis tools, forced to make their way through branded content, guerrilla marketing and spambots. How do we know they’re real? We notice it from the content these people create with brand products. From the situations they capture. The moments they choose to share. The context they let percolate.

These conversations are all the more interesting when they feature less direct opinions, less views, less sentiment that can easily fit into cookie-cutter, color coded boxes (green is positive, gray is neutral, red is bad, and so on). What we’re looking for are conversations with the proverbial “spark”, which usually arrives when we move away from the brand perimeter and enter people’s personal and social ecosystems, where brands simply become one of many factors to pay attention to.

If we interviewed ten people, we’d discover ten different stories for each brand.

Your brand isn’t what you say it is. It’s what they say it is. – Marty Neumeier in

Filling the gaps

Brand strategy, like any strategy to win hearts, must start with the understanding that to connect with people, we can’t stand in the spotlight and deliver a monologue focused solely on our own perspective.

Instead, we must look around and empathize. What do these people truly need? And what can we genuinely offer? As if by magic, by simply shifting our perspective in this way, we may discover insights about ourselves that we didn’t know before.

This approach helps us illuminate aspects of our brand that were previously unfamiliar. Only then do we know what to say—what the brand’s promise, features and purpose truly are. We understand how to reshape the message.

Only by stepping away from the abstract world of frameworks and funnels (and of stages of awareness, consideration, and conversion) can we find clearer, more coherent and ultimately more relevant solutions.

After listening to people, we are able to fill the gaps of the brief, putting our creative consultancy mission into practice. We then revisit the brief, revising and adding to it, challenging ourselves to propose something different and exploring new areas for intervention.

After talking to the target audience, we know where the brand needs to go.

PS

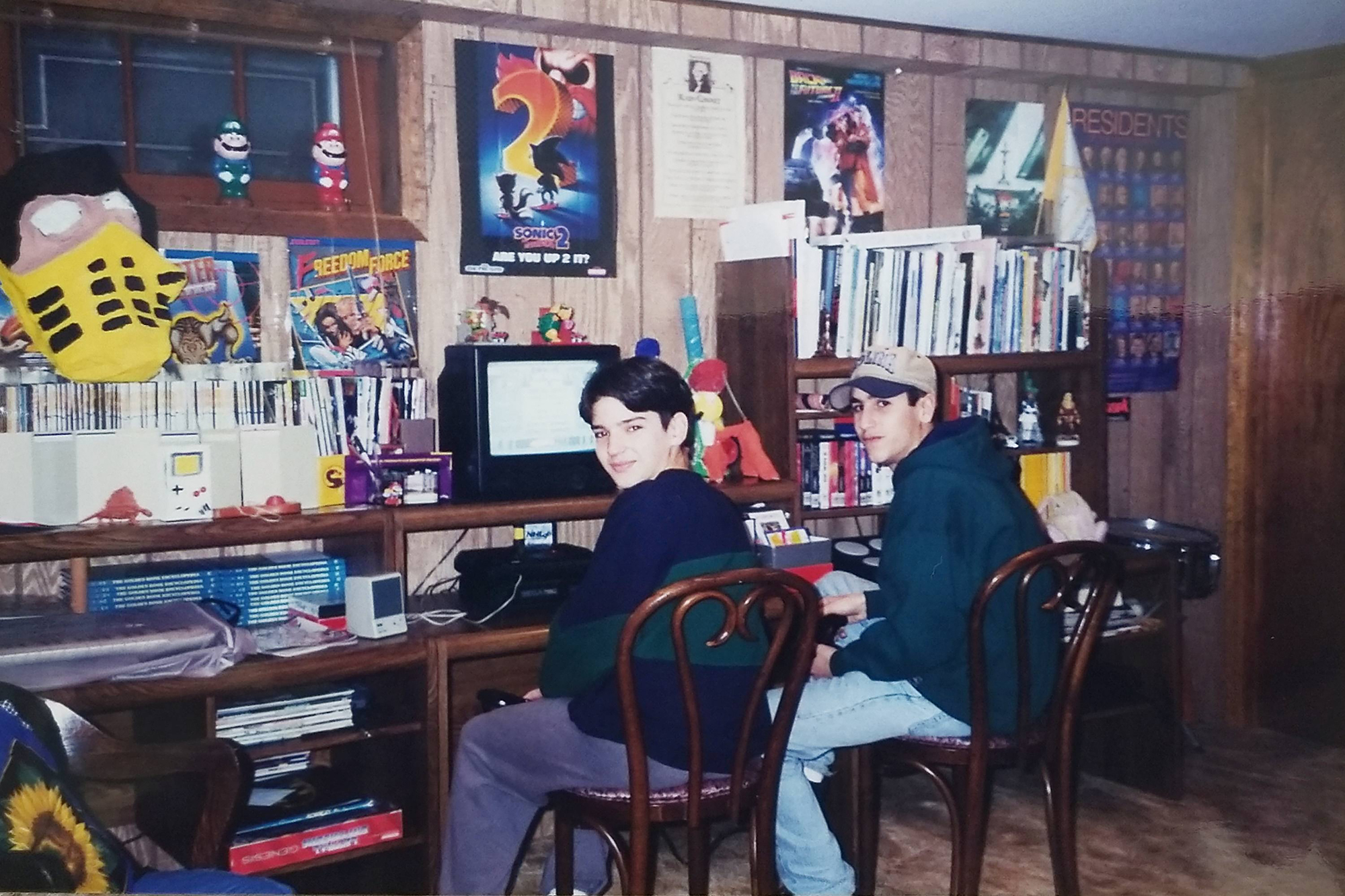

In my more than 30 years of experience as a gamer, I remember all too well the golden years of the so-called console wars, fought over graphics card upgrades and polygonal marvels housed on cartridges and compact discs, aggressively marketed through TV ads and trade magazines.

None of these features, however, remained central to a gamer's life after hitting the “Play” button. The consoles, the vessels, disappeared the moment they were turned on.

The battlefield the console war was being played out on was on a plane deeply removed from my experience as a gamer. And so I can't recall who produced the first 8 bit handheld console, the interchangeable cartridges or 3D.

I only remember the feelings of the alternate worlds punctuating my endless childhood summers, spent among the prickly pears in the Cilento region of the 1990s. The very same carefree summers I seek out whenever, in my adult life, I still feel the need to play games.