What happens when partners and creatives stop chasing the “wow” factor? A practical and theoretical guide to quality as a space for relationships.

I’m Graziano Losa, Creative Lead at I MILLE, and I’m the person everyone here expects to keep an eye on quality. Not just because we care about what we make, but because we know that, sooner or later, quality pays off. Especially for our partners.

Which brings us to the question: How does quality shape the relationship between partners and creative consultancies?

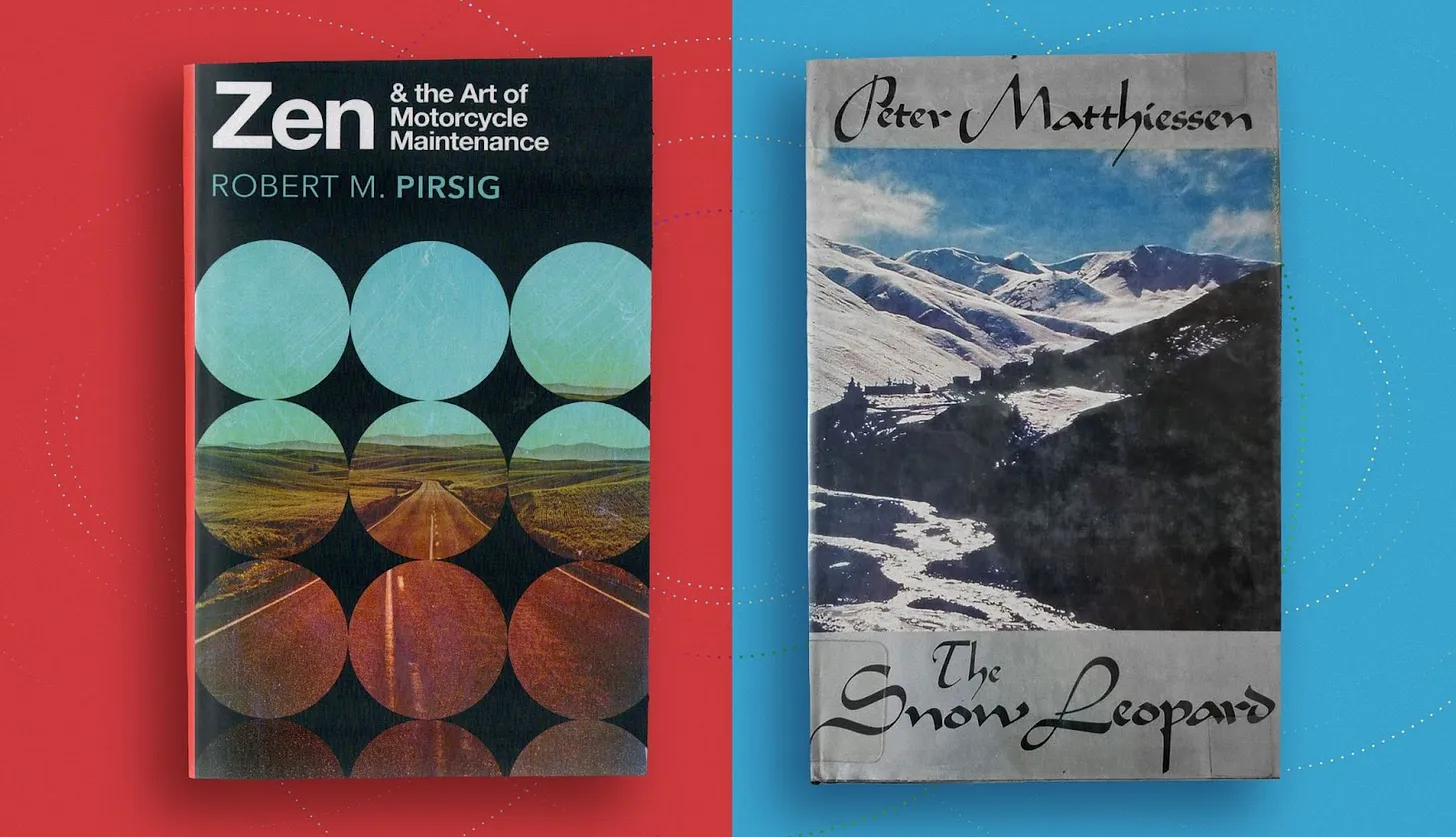

At a recent internal event, everyone at I MILLE was given 3 minutes to share a life-defining experience. My mind went straight to a book that shed new light on a question we face every day. The book is Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974) by Robert M. Pirsig, a journey both physical and philosophical, a meditation on quality that still resonates.

But quality isn’t just about output, it’s also about how we relate to one another: between creatives, consultants and partners. Here’s what I’ve learned.

You Don’t Do Quality. You Witness It.

Picture this: a creative consultancy, devoted to craftsmanship. A partner, fixated on the “wow effect”.

Both are wrong. Why?

Because quality — the “wow”, the disruption, the big idea, whatever you call it — can’t be forced.

You don’t make it happen. You don’t buy it or demand it. You experience it.

Quality reveals itself at the end of a process, not at the beginning.

The best we can do is to create the conditions that make it possible. So… how do we do that?

The 3 Metaphysical Dimensions of QualityIn his book, Pirsig lays out a theory: quality doesn’t live in the subject or the object, but in the space between. It’s a relationship. A phenomenon. A third thing.

Think of it as a 3D relationship between person and product, consultancy and partner. Here’s how he breaks it down:

1. Space

- Internal: the mental space of a relationship (thoughts, expectations, imagination).

- External: physical and environmental interaction (design, gestures, ergonomics, context).

2. Time

- Internal: the time we choose to dedicate.

- External: the time that shaped the object (materials, processes) and the time we allow for evolution.

3. Experience

- Internal + External: both lived through the five senses. Experience is how memory, emotion and meaning are built.

Applying This to Creative Consultancy

These metaphysical dimensions help us understand what “quality” looks like in our world, the world of creative consultancy.

- Space is where we assert our voice and our point of view, giving shape to a shared mental and creative territory.

- Time is the gift our partners give us: time to explore, to refine, to make mistakes, that is to let quality emerge.

- Experience is what ties everything together: the memory of the journey, the co-authored decisions, the mutual pride in the result.

So, What Does This All Mean?

Quality = Happiness.

Truly quality work is never a solo act.

It’s the outcome of an authentic, collaborative process between partner and consultancy. It grows through trust, shared effort and clarity of intention.

Quality is what happens when:

- A consultancy gets to express its identity and its craft

- A partner is involved, not just informed

- Everyone invests the right amount of time and care

- And the whole relationship is built on mutual trust

Happiness is the natural result of work done the best way possible, in the time it deserves, with the right people.

The alternative? Mediocrity.

And no one wants that.

Beyond Zen: Kōans and Haikus

There’s another book that’s just as dear to me as Zen: The Snow Leopard (1978) by Peter Matthiessen. It’s also about searching for something invisible.

As the narrator treks through the Dolpo region of Nepal, the quest for the snow leopard becomes a metaphor for chasing something elusive and unknowable.

In the book, we encounter kōans, paradoxes not meant to be solved, but lived. Like this one:

“Have you seen the snow leopard?”

“No!”

“Isn’t it wonderful?!”

Or another one invented by Paolo Cognetti:

“Who has seen Mount Kailash from the untouched summit of the Crystal Mountain?”

The answers (“the wind,” “the moon,” “a cloud”) all make sense without resolving the paradox.

But they require us to accept something irrational: that these natural elements can see.

Pirsig, too, offers us kōans:

“What’s the difference between seeing a motorcycle as a set of parts and seeing it as a whole?”

Small Forms, Big Meanings

Both books also feature haikus, short poems that capture space, time, and sensation in just three lines.

From The Snow Leopard:

“Cloud-men beneath loads.

A black trail in the white snow.

Suddenly: nothing.”

From Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance:

“Mountains in the sun.

A humming of machines.

The road disappears.”

Kōans and haikus are tiny forms that open vast perceptions. They create resonance. They connect people. They free the imagination. Just like great projects do.

So I’ll leave you with Pirsig’s final question in Zen:

“What is quality? How can you tell, if there’s no clear definition?”